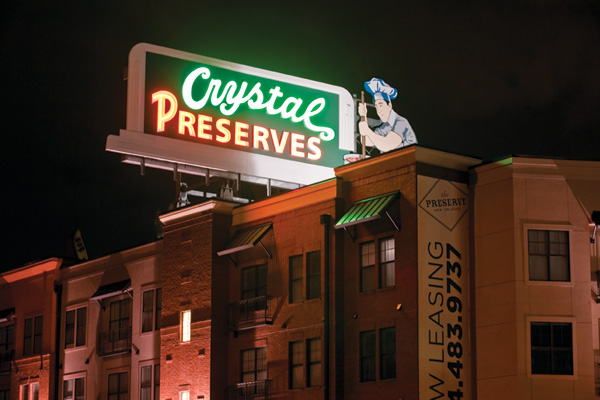

Developers Matt Schwartz (BSM '99) and Chris Papamichael (BSM '96) have built three large apartment buildings along Tulane Avenue, including the Preserve, a $45 million mixed-income development on the site of the former Crystal Preserves manufacturing plant.

Matt Schwartz fell in love with New Orleans as an undergraduate at Tulane University, but when the time came for him to graduate, the thought of staying in the city and starting a business never crossed his mind.

“I just didn’t think of New Orleans as a place where there was a lot of business opportunity,” Schwartz says. “I loved the city as a place to go to Jazz Fest and eat and enjoy the music, culture and history, but I didn’t necessarily associate it with opportunity.

He pauses.

“I think that’s changed.”

If New Orleans is really a better place to live and work than it was a decade ago, entrepreneurs like Schwartz (BSM ’99) and Chris Papamichael (BSM ’96) can take some of the credit.

Schwartz and Papamichael, principals of the Domain Companies, have invested nearly $150 million in an ambitious plan to help revitalize a long-neglected swath of New Orleans and turn it into a live/work/play destination. In the last 12 months, they’ve completed three new Class A apartment complexes along Tulane Avenue in Mid-City—the Preserve, a 183-unit mixed-income development on the site of the former Baumer Foods/Crystal Hot Sauce plant; the Crescent Club, a 228-unit mixed-income, mixed-use complex on the site of the former Crescent City Motors; and the Meridian, a 72-unit affordable-housing development on South Jefferson Davis Parkway, a block off Tulane—and they recently broke ground on a $5-million retail development across the street from the Crescent Club.

It’s a strategy the partners hope will earn them a premium as the area rebounds, but it’s also a strategy rooted in something beyond financial returns.

“We want to be in communities where we can make an impact, where we can be invested for the long term and transform that community over the long term,” Schwartz says. “At the same time that we’re doing good and improving the community, we’re profiting from the development, the growth and the upside in the community.”

In short, conscious capitalism in action.

Schwartz and Papamichael grew up a stone’s throw from each other in Syosset, N.Y., but didn’t meet until they became fraternity brothers at Tulane. Both were majoring in finance, and both aspired to real estate careers in New York.

Schwartz went to work for the Related Companies, one of New York’s largest real estate investment firms, where he specialized in affordable and moderate-income government-assisted housing. Papamichael went to work as an acquisitions officer for W&H Properties, owners of the Empire State Building, and later as a luxury condominium developer.

Combining Schwartz’s expertise in financing with Papamichael’s background in architecture and construction, the pair teamed up in 2003 to form the Domain Companies, a multifamily development firm specializing in large mixed-income, mixed-use communities in urban infill environments.

One of the firm’s first big jobs was redeveloping the sprawling Markham Gardens public housing project in Staten Island, N.Y., into a mixed-income community, a $65-million project that utilized twelve different financing sources, including tax-exempt bonds, tax-abatement certificates, and low-income housing tax credits. Designed with environmentally sustainable, energy efficient and green building techniques, the development was one of the first in the country to win approval from the U.S. Green Building Council—the organization that administers the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program—to take part in its “LEED for Homes” initiative.

Schwartz and Papamichael had actually been trying to advance a market-rate condominium project in New Orleans immediately prior to Hurricane Katrina. Less than 30 days after the storm hit, they were back in New Orleans, surveying the damage and trying to figure out how—or if—they could participate in the recovery.

“We definitely wanted to help the city come back, but at the same time it had to make business sense,” Schwartz says. “A lot of the lenders were looking at New Orleans and saying, ‘Convince us this won’t be downtown Detroit five years from now.’ We were asking ourselves the same question: Does this make sense apart from the fact that we love New Orleans and want the city to come back? We thought it did.”

Nearly 80,000 homes in New Orleans were destroyed by Katrina, including much of the city’s affordable housing stock. Schwartz knew immediately there would be tremendous demand for housing, but he also recognized that the availability of federal disaster recovery funds would make large mixed-income, mixed-use developments—the developments Domain specializes in—feasible in New Orleans for the first time.

The question of where to put those developments was never really a question. From the beginning, Schwartz and Papamichael zeroed in on Tulane Avenue.

With its blighted storefronts, rundown motels and 24-hour bail bond shops, Tulane Avenue might not sound like an obvious choice for high-end apartments, but Schwartz and Papamichael saw something else. They saw a valuable commercial strip that intersects virtually every major thoroughfare in New Orleans. It was close to downtown, making it an ideal location for renters hoping to live closer to work, and there were several large sites available for development, enabling Schwartz and Papamichael to realize the economies of scale they look for.

Not lost on the developers was the fact that Tulane Avenue runs through the heart of the Greater New Orleans Biosciences Economic Development District, the proposed site of a new VA/University Medical Center hospital complex that could bring thousands of high-paying jobs to the neighborhood in the next 10 years.

To move the developments forward, Schwartz and Papamichael not only had to sell city and state officials on their vision of a revitalized Tulane Avenue, they had to help them design the financing programs to make it possible. Beginning in 2006, Schwartz visited Baton Rouge on an almost weekly basis, meeting with lawmakers and officials from three different agencies— the Louisiana Recovery Authority, the Louisiana Housing Finance Agency and the Office of Community Development—to secure GO Zone tax credits and Community Development Block Grant funds. They flew investors in from New York to make their case for the future of the New Orleans market, and they flew them in again to show state officials that their proposals had the support of the investment community.

The Domain Companies wasn’t the only firm trying to develop housing in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, but they were one of the few to stick with it despite seemingly endless roadblocks and delays.

“Had we not loved New Orleans so much, it would have been a lot easier at many points throughout the process to just walk away,” Schwartz says. “People we know came to us and said, ‘What’s the deal? You can’t get anything done here.’ And we said honestly you know it’s not like working other places. A lot of what you take for granted elsewhere is a challenge here, but at the end of the day you can get it done.”

Mixed-income developments can take various forms, but Schwartz and Papamichael’s New Orleans developments are designed with 60 percent market-rate units and 40 percent workforce housing, a category of affordable housing restricted to individuals earning no more than 60 percent of the area’s median income. While the affordable housing component enables Domain to take advantage of tax credit financing and other incentives, Schwartz says it’s not the only reason Domain opts for mixed-income developments.

“We just think that mixed-income, mixed-use developments result in more sustainable, more vibrant communities,” he says. “It takes a number of components to make a community work and grow and develop and thrive, and I think you need to have all of those for a community to be successful. We try to bring all of that to the table.”

Both the Preserve and the Crescent Club, above, feature resort-style center courtyards with swimmings pools and Wi-Fi, furnished clubhouses for entertaining, and fully equipped fitness centers.

On the market-rate side, Domain targets the so-called renter by choice, the professional who could buy or rent a house but chooses to live in an apartment for the convenience and service.

“We’re getting a lot of people who work in downtown office jobs who were living in Harahan or Kenner in what would be considered Class B multifamily,” Schwartz says. “They can move up to Class A at the same rent or a slight premium and be much closer to downtown. Value-wise, our product is far more attractive because we include extensive amenities and services to create a very convenient lifestyle.”

The Preserve and the Crescent Club each feature a resort-style central courtyard with swimming pool and Wi-Fi, a clubhouse for entertaining, a fully equipped fitness center, a business center, secure parking, and on-site management. The Meridian features those same amenities with the exception of a pool. All three properties feature a suite of convenience services including online rent payment, online maintenance requests, concierge service, daily continental breakfast in the clubhouse, a newsletter, and special events and activities for residents like cooking classes or Saints game day parties. Residents also receive a “My Domain Rewards” card, which offers discounts at area merchants.

Mixed-income housing was a new, largely untested model in New Orleans when Domain first proposed it, and some locals questioned whether Domain would be able to attract market-rate tenants willing to live alongside affordable-housing renters, but the results speak for themselves. All three properties were 100 percent leased within months of opening.

“You look at our developments versus a 100 percent market-rate development like the Saulet, and we have better layouts, better finishes, bigger kitchens, more cabinet space, better amenities and better all around service,” Schwartz says. “Is it really weighing into people’s decision making that there are people who work as teachers or first-responders living next door? We’re not seeing it.”

In addition to winning the support of state officials, they also won the support of neighbors, many of whom were initially skeptical about the affordable-housing component. Schwartz and Papamichael met with the Mid-City Neighborhood Association to present their plans and answer questions, but they went a step further.

They bought 30 blighted houses and lots in the neighborhood surrounding the Preserve site, renovating and selling some and turning others into community gardens for residents. They purchased the former Gold Seal Creamery, a block from the Preserve, and announced plans to redevelop it. They funded the restoration of nearby St. Patrick’s Park to give residents a place to play softball and kickball.

When they realized there weren’t many dining options within walking distance of the Preserve, Schwartz and Papamichael bought and renovated a couple of dilapidated commercial buildings on Banks Street, three blocks from the Preserve, and rented them to the owners of Huevos, a cozy breakfast café, and Crescent Sausage & Pie Co., a gourmet pizza restaurant. Today, those restaurants are helping to spur a commercial renaissance on Banks Street, which Schwartz and Papamichael envision becoming a retail strip similar to Oak Street or Maple Street.

“From a business perspective, that’s not our core business and it’s not a tremendously profitable business for us,” Schwartz says. “Where we do see the return is we’re starting to see other commercial and residential buildings throughout the neighborhood get renovated by outside investors, which is improving the area and as a result we’re seeing the value of our properties appreciate. So that’s how we measure success.”

That sort of thinking is also behind the Shops at Crescent, the $5 million retail development Domain is building across from the Crescent Club. The shopping center will add 18,000 square feet of retail to the neighborhood, including a bank, a dry cleaner, a nail salon, a Subway sandwich location, a pizza place and a coffee shop as well as a wine and tapas bar featuring live jazz.

Schwartz says it took the Domain Companies nearly two years to lease the retail space, not because retailers weren’t interested but because Domain wasn’t interested in renting to just anyone.

“We wanted to bring into the area basic and critical retail services for our residents, but we also wanted to provide the amenities that would make this neighborhood the kind of neighborhood we’re trying to create,” Schwartz says. “We’re trying to engineer that retail to create the kind of environment people are looking for and spark additional development in the area.”

In June 2006, Schwartz and Papamichael opened a permanent office on South Peters Street in the Warehouse District, signifying their long-term commitment to playing a role in the future development of New Orleans. While Schwartz says he and Papamichael have a number of new developments in the works, their focus right now remains squarely on Tulane Avenue.

“The future of the city from an economic development perspective rests in this 25 block area,” Schwartz says. “A lot of the issues that the city has had in many different areas—whether it’s education, crime or housing—relate back to incomes and the availability of stable, well-paying jobs. As those hospitals are developed, we think biosciences-related development as well as additional housing and retail services will continue to fill in the area. This area will continue to develop as a thriving mixed-use district, and we will continue to develop projects that enhance this neighborhood as a place to live, work and play.”