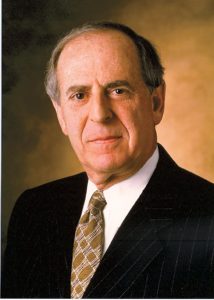

Reflecting back on the start of his career, Al Goldman (BBA ’56) doesn’t hesitate when asked what advice he’d give to current students starting their careers.

“Don’t know you’re applying for a job,” he laughs. “You can really be yourself.”

After earning a business degree from Tulane and spending two years in the Navy, Goldman returned to his hometown of St. Louis in 1958 and enrolled in the clinical psychology PhD program at Washington University, but he soon realized the academic life wasn’t for him. Out of school and out of work, he needed a job.

Goldman’s father was friends with Presley Edwards, chairman of A. G. Edwards & Sons, the St. Louis-based securities firm, so to help his son out, he set up an appointment for Al with the executive.

“I thought I was coming down for some Dutch uncle advice,” Goldman recalls. “He apparently thought I was coming down to apply for a job. When it was time to leave, I thanked him for the time and advice he’d given me. He said, ‘What do you mean thank you? Be here tomorrow at 7 o’clock.’”

That interview-that-wasn’t-an-interview was the start of a 50-year career as a securities and market analyst, writer and lecturer on investments. Goldman spent 48 of those years with A. G. Edwards, eventually becoming chief market strategist for the firm and serving as corporate vice president and a member of the executive committee and board of directors.

When Goldman started his career, most brokerage firms focused almost exclusively on long-term investing. Goldman had a hunch that some clients might want to be more aggressive with a portion of their portfolios, so he came up with the idea of identifying a small number of stocks and pitching them to investors seeking aggressive short-term returns. The concept was a hit with clients, and picking those short-term winners became a big part of Goldman’s job.

“When you’re looking out only six months, this is not long-term investing; this is trading,” he says. “You have to pay maximum attention to the market itself.”

Goldman struggled to find the right approach. He started out doing fundamental analysis and that worked some of the time, but it didn’t explain how the market could go down despite strong economic news. Next he turned to technical analysis, focusing on charts and market history, but again he found that past results didn’t always predict future performance.

Then Goldman had a breakthrough, and he owed it to his study of abnormal psychology.

“It seemed to me what was really going on in the market was emotions,” he says. “I went from being a fundamentalist to being a pure technical analyst to being, for lack of a better word, an emotionalist, trying to understand the mood of the market.”

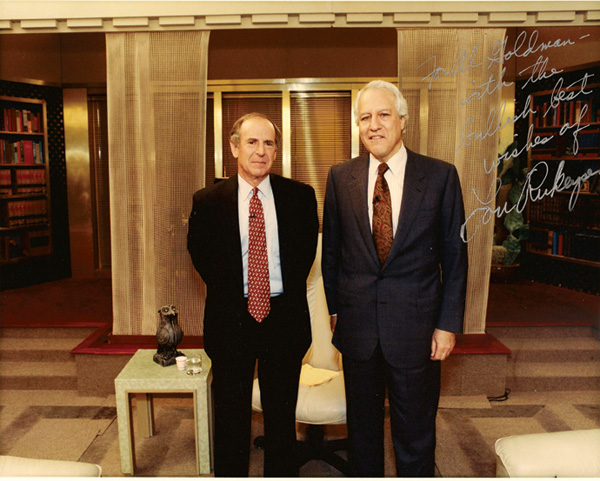

That approach—focusing on the prevailing mood of investors as they take in market news rather than news itself—helped turn Goldman into a nationally recognized market commentator. His weekly market report was published in 40 newspapers across the country, and he was quoted in publications including The Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, USA Today, Investor’s Business Daily and Bloomberg Business News as well as on ABC, CNBC, CNN, Fox News, Bloomberg TV and PBS’ “Nightly Business Report.”

“Basically, my philosophy is listen to the market, don’t lecture it,” Goldman says. “You cannot impose your opinion on the market. Ego control is, I think, the big divider between the winners and losers among market strategists.”

A.G. Edwards was acquired by Wachovia in 2007 and Wachovia was acquired by Wells Fargo in 2008. Goldman spent two years as chief market strategist with Wells Fargo Advisors, but on June 1, 2010—almost 50 years to the day after his interview with Presley Edwards—he officially retired. Goldman still follows the market, but he now has time for things like playing golf, learning to play the piano, taking classes at Washington University, and participating in programs at the Chautauqua Institution in New York.

“I know this sounds corny, but I got very lucky,” Goldman says. “I never woke up any morning—even in a bear market—where I said, ‘Oh darn, I gotta go to work.’ For the first 15 years, I was the first person in and the last one out. For the last 35 years, I was still the first person in, just not always the last out.”