When Ira Solomon was a young assistant professor at the University of Arizona, the Bureau of Indian Affairs asked him to investigate a tomato farm.

The Quechan Indians had received a federal loan to start a tomato-growing business on their reservation, located in the remote southwestern corner of the state, and the bureau asked Solomon to evaluate the business and recommend whether or not to support the tribe’s request for additional funds.

After traveling to the rugged Fort Yuma Reservation and poring over the Quechans’ finances, Solomon submitted a report highly critical of the tomato enterprise, noting that workers were grossly overpaid and the venture was unlikely ever to yield a profit.

A few days later, he got a visit from a director with the agency. “You didn’t get it,” he told Solomon. “We were looking for a much more comprehensive analysis.”

The Quechans may not have been making money on the sale of tomatoes, the director explained, but that was never the goal. The goal was to improve the lives of the Quechan people, and by providing jobs, engaging the community and helping to reduce deleterious behaviors, the tomato business was in large part achieving that goal.

A light went off in Solomon’s head. It was the young scholar’s first encounter with what would eventually come to be known as the triple bottom line, and it made a big impression.

“I never learned that in school,” Solomon says. “It was a powerful firsthand experiential learning exercise, and it helped shape my thinking.”

Today, more than 30 years later, Solomon remains committed to the notion that businesses—and business schools—have a responsibility to society, and the newly appointed dean of the A. B. Freeman School of Business hopes to instill that sense of responsibility in students.

“As a business school, our educational programs need to be geared so that students understand the context they’re going to be operating in and have a positive impact on that context,” Solomon says. “I think that perspective resonates very well with young people, and I think it fits in perfectly with President Scott Cowen’s vision for Tulane University.”

Since becoming dean, Solomon has spoken frequently about his desire to better prepare students to grapple with today’s most vexing issues, but that’s just one small part of a bigger vision for the school: Solomon hopes to make Freeman a “school of choice” for business students from around the world, a school students choose to attend not because they didn’t get into Harvard, Wharton or Yale but because it offers one of the top programs in the world in their area of interest.

“No matter where someone is located, if they’re interested in studying X, the Freeman School should be in the top five schools they think of,” Solomon says, adding that becoming a school of choice for students will help attract the best young faculty members as well. “Now we can’t be a school of choice in every area—we’re too small—so we have to be judicious about picking what areas we have a legitimate chance of emerging as a true center of excellence.”

“No matter where someone is located, if they’re interested in studying X, the Freeman School should be in the top five schools they think of,” Solomon says, adding that becoming a school of choice for students will help attract the best young faculty members as well. “Now we can’t be a school of choice in every area—we’re too small—so we have to be judicious about picking what areas we have a legitimate chance of emerging as a true center of excellence.”

And what areas should the Freeman School pick? And what strategies should the Freeman School employ to become a center of excellence in those areas? Those are among the questions that helped bring Solomon to Tulane.

“I’ve always enjoyed being in building mode and the strategizing that goes along with that—what can we do that will differentiate us from other business schools?” Solomon explains. “Working with the faculty and staff here to help devise those kinds of initiatives is something that I thought was a real opportunity. If all the Freeman School needed was a caretaker, there’d be no reason for me to be here.”

Ira Solomon officially became the 13th dean of the A. B. Freeman School of Business on July 1, 2011, culminating a nine-month national search led by Tulane Provost Michael Bernstein and Professor of Finance Sheri Tice, who chaired the school’s search committee. Solomon succeeded Angelo DeNisi, the Freeman School’s dean since 2005, who resumed his research and teaching as a member of the school’s faculty.

Dean Solomon, right, with Rick Rees (A&S ’74, MBA ’75), chairman of the Business School Council. Solomon says he hopes to have the council play a much more substantive role in the areas of placement, recruiting and strategic planning.

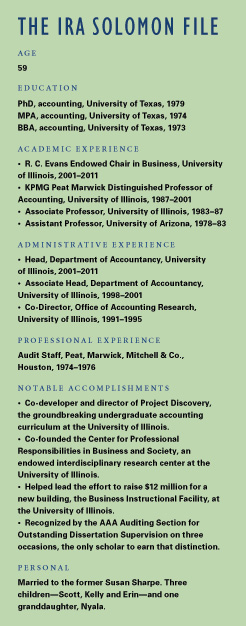

A native of New York, Solomon has built an exceptional record of accomplishment in his almost 35-year career as a teacher, scholar and academic administrator. Prior to his appointment as dean, Solomon was the R.C. Evans Endowed Chair in Business and head of the Department of Accountancy at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he was a primary architect in creating what is widely regarded as one of the nation’s finest accounting programs.

Solomon is also a leading scholar in his field, with more than 35 academic articles, monographs and books on auditing and assurance services to his credit. He has testified for and served as an expert adviser to numerous private firms as well as the Securities & Exchange Commission, the Department of Justice and the Department of the Treasury. In the classroom, Solomon is the only accounting professor to be recognized by the AAA Auditing Section for Outstanding Dissertation Supervision on three separate occasions.

According to Provost Bernstein, Solomon embodies all of the characteristics the university was looking for in a new business dean: knowledge, experience, enthusiasm, vision and, perhaps most significantly, a profound understanding of the mechanics of business education.

“Ira knows how outstanding business schools work,” Bernstein says. “He has a powerful grasp of all aspects of the operation. From the level of the bridge, standing at the helm, all the way down to the engine room, he knows how the ship runs, and that’s important.”

“He’s a problem solver and a strategic thinker,” adds Rick Rees (A&S ’74, MBA ’75), chairman of the Business School Council. “He’s collaborative in his decision-making process, but he isn’t afraid to make tough decisions. He won’t support a compromise position if he feels strongly that it isn’t the right position.”

“Ira is a visionary,” says A. Rashad Abdel-khalik, director of the V. K. Zimmerman Center for International Education and Research of Accounting at the University of Illinois and a longtime friend and colleague of Solomon. “When he was here, he was the strongest department head in the College of Business because he could look across departments and disciplines in ways that others couldn’t and see opportunities for integration. “Ira changed things dramatically here, but I think he needed something new to be satisfied,” Abdel-khalik adds. “Tulane is lucky in that sense. The opportunity came at the right time.”

Solomon was born in New York City and grew up in the suburban hamlet of Roosevelt on Long Island, where his neighbors included Howard Stern and future NBA Hall of Famer Julius Erving.

When he was a senior in high school, Solomon set his sights on attending the University of Texas at Austin, home to one of the nation’s finest accounting programs. To earn money for college, he quit his high school baseball team (he played third base and pitched) and got a job at a printing company. Every day after school, Solomon would head to a nearby industrial park, where he worked until 11 o’clock at night as an assistant paper cutter, the lowest rung on the union shop’s chain of command.

When he was a senior in high school, Solomon set his sights on attending the University of Texas at Austin, home to one of the nation’s finest accounting programs. To earn money for college, he quit his high school baseball team (he played third base and pitched) and got a job at a printing company. Every day after school, Solomon would head to a nearby industrial park, where he worked until 11 o’clock at night as an assistant paper cutter, the lowest rung on the union shop’s chain of command.

“I was in Local 1 of the Printers Union, which was a very powerful union at the time,” he says with a laugh. “It was a very interesting operation. I learned a lot there, to say the least.”

While the promise of a good job and a comfortable living was appealing, Solomon was attracted to accounting for philosophical reasons as well. Accounting facilitates the flow of capital to its most productive uses, he says, which benefits society, but accounting also provides individuals with the tools to get to the bottom of virtually any issue.

“I learned early on there’s tremendous wisdom in the old saying, ‘Follow the money,’” Solomon says. “Accounting builds the ability to follow the money, to peel apart these ridiculously complex footnotes and learn what’s really happening. That’s something I’ve internalized. Whether it’s a university setting, any of the volunteer work that I have done or for professional organizations, I’ve learned that if you can learn where the money flows, you can really understand the institution a lot better.”

After graduating from the University of Texas, where he met his wife, the former Susan Sharpe, Solomon spent nearly two years on the audit staff of Peat Marwick in Houston before deciding he wanted to try something new. He had enjoyed the research and writing while working on his master’s degree in accounting, so with Susan’s support, he made the leap to academia and enrolled in the doctoral program at the University of Texas. In 1979, he graduated with a PhD in accounting. His dissertation was entitled Aggregating Prior Probability Distributions for Audit Decision Making.

After earning his PhD, Solomon spent five years as an assistant professor at the University of Arizona before joining the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign as an associate professor in 1983. Solomon became a full professor in 1987 and co-director of the university’s Office of Accounting Research in 1991. It was in that role that Solomon first began to think about the growing disconnect in accounting education.

The information technology revolution had fundamentally changed the way businesses operate, yet accounting education for the most part was still rooted in the paradigms of the past. While companies were increasingly leveraging intangibles like logistics, processes, software and human capital to generate value, accounting textbooks still stressed old economy assets like machinery, plants and inventory. While accountants were increasingly being asked to serve as consultants and perform complex non-financial audits, accounting courses still stressed rigid rules and single-answer solutions.

“My view was that accounting needed to be remade for the era that was emerging, one in which value was being created by businesses in a very different way,” Solomon says. “At the end of the day, what the accountant does is help signal to the suppliers of capital where they can get the greatest bang for the buck, and if accounting loses the ability to create an accurate such signal, then capital flows to less productive uses and society is the worse for it.”

“My view was that accounting needed to be remade for the era that was emerging, one in which value was being created by businesses in a very different way,” Solomon says. “At the end of the day, what the accountant does is help signal to the suppliers of capital where they can get the greatest bang for the buck, and if accounting loses the ability to create an accurate such signal, then capital flows to less productive uses and society is the worse for it.”

The University of Illinois’ accounting program was ranked No. 1 in the nation at the time, but that didn’t stop Solomon and his team from scrapping the entire curriculum and starting over from scratch.

“We decided we couldn’t fix it,” Solomon says matter-of-factly. “We couldn’t migrate from where we were to where we wanted to go, so we created a completely new one.”

Project Discovery, the new curriculum that Solomon co-developed and directed, reinvented undergraduate accounting education with a fresh approach that emphasized new value creation, problem solving, critical thinking, communication and teamwork. The curriculum eschewed textbooks in favor of case studies, simulations and group projects designed to encourage students to analyze complex issues and develop their own solutions.

In one class project, Solomon asked students to come up with a way to verify that the fictitious Dave’s Dating Service was providing a high quality of service to its customers. Students were tasked to come up with unique measures—such as comparing the income of customers to the general population—that the company could use to demonstrate value and attract new clients.

Solomon speaks with New York alumni in September at one of several events organized to give alumni an opportunity to meet the dean.

Since its introduction in 1997, Project Discovery has kept the University of Illinois at or near the top of every undergraduate accounting ranking in every year since, students have continued to pass the uniform CPA exam in great numbers and the curriculum has become a model for other institutions, including Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. In addition, graduates of the program have become hot commodities in the job market, with students being hired by a wide range of employers that had previously shied away from accounting majors.

In addition to directing Project Discovery, Solomon was also a successful fundraiser at Illinois. He helped raise more than $12 million for the construction of a new building, the Business Instructional Facility, and he co-secured a $4 million gift from the Deloitte Foundation and a $4 million settlement from the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois to endow the Center for Professional Responsibilities in Business and Society, an interdisciplinary research center dedicated to promoting professional responsibility and accountability in individuals and organizations.

When Solomon was first contacted by Tulane’s search firm about the possibility of becoming a candidate for the dean’s job, he responded the same way he always did to such inquiries: Thanks. Not interested.

Solomon with Joe Traina (BSM/MAACT ’06), left, and Associate Dean Mike Hogg at September’s Freeman Days New York Networking Reception.

To say Solomon had little desire to leave Illinois at the time is putting it mildly. He was head of one of the nation’s top-ranked accounting programs, a program he had personally played a major role in designing. He held one of the largest endowed chairs on campus, giving him uncommon freedom to pursue his research and teaching interests. He was a highly respected figure in the business community, serving as an adviser to government agencies and a frequent guest at industry events. And he and Susan were well-established as residents of Urbana, where they had lived and worked for 28 years.

“I was in a great place,” Solomon says. “I was having a good time. Why should I think about leaving?”

The search firm was persistent, however, and when it contacted him a third time, Solomon relented and agreed to submit a resume with no obligation. He didn’t think about it again until a few weeks later, when the search firm asked him to come down to New Orleans for a visit. That began a process Solomon likens to a seduction.

The more Solomon learned about Tulane and the Freeman School, the more he began to realize it was a very special, even unique, opportunity. He shared Tulane President Scott Cowen’s commitment to public service and community engagement, he was impressed by the quality of people he met at the school and university during the interview process, and he was encouraged by the level of support and freedom being pledged to the business school. At the same, he and Susan had recently become empty nesters, and with the birth of a grandchild—their first—to their son and his wife in Houston, the Gulf South suddenly became an attractive destination.

Most of all, however, Solomon saw in the Freeman School an opportunity to make a difference. No other business school in America had gone through what the Freeman School went through in the wake of Katrina, but after six difficult years of recovery, years marked by tightly controlled budgets and limited resources, the Freeman School was poised for rapid growth and in need of a dean with the knowledge and experience to guide that growth.

Most of all, however, Solomon saw in the Freeman School an opportunity to make a difference. No other business school in America had gone through what the Freeman School went through in the wake of Katrina, but after six difficult years of recovery, years marked by tightly controlled budgets and limited resources, the Freeman School was poised for rapid growth and in need of a dean with the knowledge and experience to guide that growth.

“People here have had their heads down, working very, very hard, for a number of years,” Solomon says. “We now need to go to the next stage of recovery in which there are more people with a shoulder to the proverbial wheel and where we can look up and think more about what we can do to grow. I find these kinds of environments exciting. If this were 15 years down the road and all this had been done already, I’d probably still be back at Illinois.”

Solomon wasted no time getting started. He arrived on campus in June—a month ahead of schedule—and set up individual meetings with every professor on the faculty to hear their thoughts and discuss ideas. He met with the Business School Council, the Freeman School’s advisory board, and told them of his desire to have the group play a much more substantive role in school planning, recruiting and placement efforts. He initiated the strategic planning process, setting up faculty committees to examine a host of issues, everything from finding space for faculty and students to identifying programs and specialty areas with potential for growth.

But before acting on any recommendations or doing anything else, Solomon says one thing needed to be addressed: The Freeman School’s critical shortage of tenured faculty.

One of Solomon’s first acts as dean was to appoint Paul A. Spindt, Keehn Berry Chair of Banking and professor of finance and economics, as senior associate dean. Spindt, above left, is working closely with Solomon to coordinate the recruitment of 15 new faculty members over the next two years.

In the wake of Katrina, Freeman lost a number of faculty members. Now, with enrollments back at or above pre-Katrina levels across all programs, the Freeman School finds itself with a significant shortage of tenured and tenure-track professors. To get to the next level—to become a school of choice—Solomon says it’s essential for Freeman to bring the size of its faculty into line with that of peer institutions.

“The school right now is grossly underfacultied,” Solomon says bluntly. “If the Freeman School is going to continue to realistically have the same aspirations that it states it has on paper, we are going to have to hire a very large number of faculty over the short term.”

In October, Solomon announced an ambitious plan to hire 15 additional tenure-track faculty members over the next two years, an effort that will increase the size of the Freeman School’s faculty by a remarkable 40 percent.

While that prospect might sound daunting, Solomon says it represents an extraordinary opportunity to reinvigorate and revitalize the business school.

“An increase of 40 percent is a massive infusing of intellectual capital,” Solomon says. “This is our chance to remake the Freeman School faculty for decades to come and to put us on an even higher trajectory, and it’s something I find most interesting and exciting.”

And that prospect has a lot of people at the university interested and excited.

“I can’t emphasize enough the excitement everyone feels about Ira joining us,” says Provost Bernstein. “He’s inspiring people. He’s grappling with some key challenges and coming up with, I think, quite artful and ingenious solutions. He’s got great energy and passion. I think he’s going to be one of the great deans in the history of the school. I’m just excited to think about what the Freeman School is going to look like two years from now under his leadership. It’s going to be a very exciting journey.”