The dean of one of Mexico’s top business schools doesn’t mince words.

“I don’t think any U.S. business school has done as much to further the development of business education in Latin America as the Freeman School,” says Mauricio Gonzalez, dean of the Northern Region for the School of Business at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (ITESM). “Tulane’s reputation in Latin America is outstanding.”

Gonzalez should know. He’s not only dean, he’s also a Tulane graduate: He earned his PhD in management from the Freeman School in 2000.

Over the last 20 years, the Freeman School has awarded 85 PhDs to business professors in Latin America, more than any other U.S. institution. While that fact alone makes Freeman one of the most prominent U.S. business schools in the region, the Freeman School’s influence is perhaps even greater. Of those 85 PhD graduates, 30 now serve as deans, directors or senior administrators at leading Latin American business schools. Not coincidentally, many of those schools are now Freeman partner institutions, collaborating with the Freeman School to deliver high-quality graduate programs that are taught jointly by their faculty and faculty from Freeman.

The benefits of joint programs are many. The Latin American institutions get to offer students a more rigorous and attractive program than they could otherwise. Freeman gets to participate in a growing market and broaden its teaching and research. Tulane gets to build its name recognition and reputation throughout the region. And students get the bonus of earning two degrees: A master’s degree from their home university and a master’s from the Freeman School, a highly prestigious credential for Latin American students.

The benefits of joint programs are many. The Latin American institutions get to offer students a more rigorous and attractive program than they could otherwise. Freeman gets to participate in a growing market and broaden its teaching and research. Tulane gets to build its name recognition and reputation throughout the region. And students get the bonus of earning two degrees: A master’s degree from their home university and a master’s from the Freeman School, a highly prestigious credential for Latin American students.

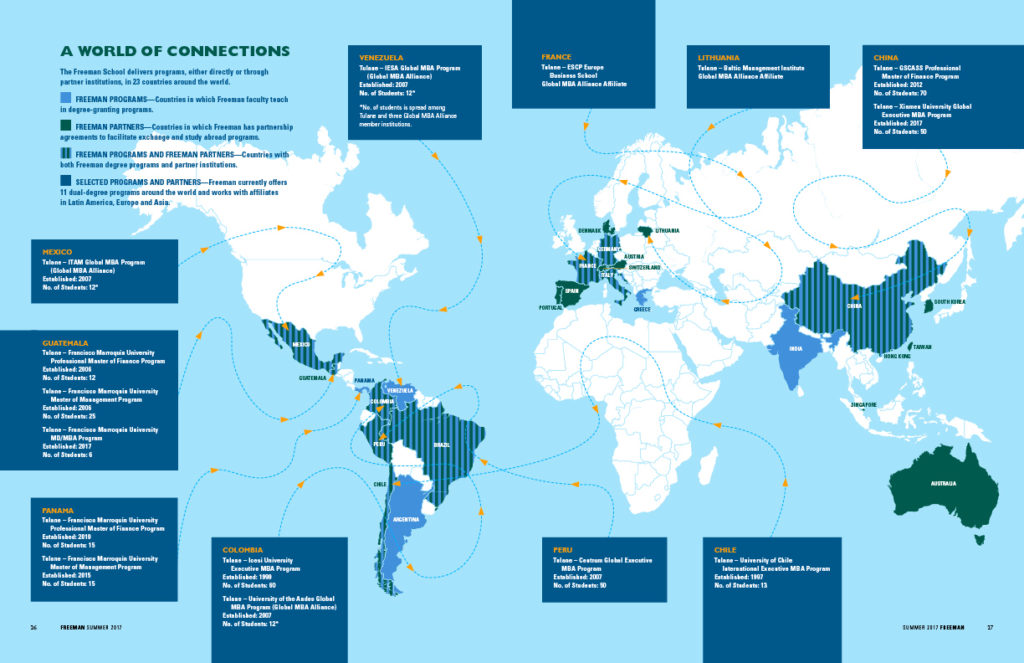

Freeman currently offers nine different dual-degree programs in partnership with Latin American business schools. These range from executive MBA programs for students in Chile, Peru and Colombia to Master of Management offerings for students in Panama and Guatemala to a unique Master of Global Management program that brings students from Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela together with students in the Freeman School’s full-time MBA program.

Those Latin American offerings are in addition to two dual-degree programs in Asia: A Global Executive MBA program offered in conjunction with Xiamen University in Xiamen, China, and a Professional Master of Finance program run in partnership with the graduate school of Beijing’s prestigious Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. With the GSCASS MFIN program, Tulane is one of just a handful of U.S. institutions with a program approved by the Chinese Ministry of Education.

All together, nearly 350 students outside the U.S. are currently enrolled in Freeman School degree programs. Thanks in large part to those programs, Freeman now has more than 1,500 alumni in Latin America and another 1,300 in China.

Mahesh Rajan (MBA ’16) shot this photo of the Shanghai skyline during the 2016 Global Leadership trip to China.

But international dual-degree programs are just one facet of the Freeman School’s global reach. Freeman has also developed bilateral partnerships with more than 35 universities in 17 countries around the world. These long-running relationships form the basis of Freeman’s phenomenally popular study abroad program, which each year sends over 180 students to universities around the world while bringing in a roughly equal number to study at the Freeman School. The Freeman School is the only unit of Tulane to administer its own study abroad program, a distinction that enables Freeman to focus on partnering with the best business schools in each country.

When you combine international dual-degree programs and study abroad opportunities with the MBA program — which remains the nation’s only program to feature course-based travel to three international locations — one can make a strong case that Freeman is one of the most international business schools in America.

How did a relatively small business school school tucked away in New Orleans become such a major international player?

The answer, or at least part of it, goes back to the Freeman School’s founding. In the early 1910s, the New Orleans Association of Commerce felt strongly that the city was poised to become a center of international trade. That belief was more than just an idle hope. With the Panama Canal set to open in 1914, trade between South America and the U.S. was projected to grow substantially, and the Port of New Orleans was expected to be a major beneficiary of that uptick.

Goldring Institute Executive Director John M. Trapani III, center, began developing the Freeman School’s international strategy nearly 30 years go.

To fully leverage this new opportunity, however, the Association of Commerce believed the city’s business people — everyone from bankers to barge operators to coffee brokers — would need additional education. To ensure the availability of that training, the members of the association partnered with Tulane University to underwrite the founding of a new business college, the first collegiate school of business in the Gulf South. Tulane’s College of Commerce and Business Administration began offering classes to working professionals in New Orleans in October 1914, just weeks after the SS Ancon became the first ship to pass through the Panama Canal. Not coincidentally, two of the first five courses offered by the College of Commerce were devoted to international business: Commercial Spanish and Foreign Trade, which promised “a study of the needs of foreign markets for goods produced in this country and of the products of those countries in which a reciprocal import trade should be developed.”

International business continued to occupy a central place in the business school’s curriculum for the next 70 years, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that the Freeman School first began to export its programs to students outside the U.S. The credit for that decision lies in large part with a soft-spoken Texan who’s spent the last 30 years quietly laying the groundwork for Freeman’s widening international footprint.

When John M. Trapani III began developing international programs at the Freeman School in 1989, he had two goals in mind: To provide learning opportunities for students in international locations and to position Freeman as a leader in the development of business education around the world. Three decades later, it’s hard to argue with the results.

“We probably have the most impact in Latin America of any other American or European university, and we have some very unique, highly regarded programs in Asia as well,” says Trapani, who today serves as the Martin F. Schmidt Chair of International Business and executive director of the Goldring Institute of International Business. “You don’t hear that unless you’re there a lot of the time, but you hear it at meetings where Latin Americans are represented and you hear it when Chinese talk about American business schools in China.”

“We probably have the most impact in Latin America of any other American or European university, and we have some very unique, highly regarded programs in Asia as well,” says Trapani, who today serves as the Martin F. Schmidt Chair of International Business and executive director of the Goldring Institute of International Business. “You don’t hear that unless you’re there a lot of the time, but you hear it at meetings where Latin Americans are represented and you hear it when Chinese talk about American business schools in China.”

“I think what stands out most about our international programs is that they’re rooted in institutional development,” adds Freeman School Dean Ira Solomon. “Virtually all of our dual-degree offerings in Latin America and Asia were established to help partner institutions deliver educational programs that wouldn’t otherwise be available. That was true when we developed our very first international programs, and it remains true today thanks in great part to the work of Professor Trapani.”

Former Dean James W. McFarland hired Trapani, then chair of the economics department at the University of Texas at Arlington, to be his associate dean for international programs in 1989. The title, however, was a bit of a misnomer: With the exception of a study abroad program McFarland had started the year before, the Freeman School didn’t have any international programs at the time.

Together, McFarland and Trapani set out to change that.

In 1990, they accepted an invitation to help establish a new business school in Hungary, which was then in the process of transitioning from communism. The International Management Center in Budapest became the first Western-style business school in Eastern Europe. In addition to teaching, Trapani designed the school’s executive MBA curriculum. Two years later, McFarland and Trapani returned to Eastern Europe to help establish a second Western-style business school, the Czech Management Center in Prague.

“I taught the very first economics classes, and we used a lot of our faculty to teach over there,” Trapani recalls. “When you think about Freeman international ventures, that was the very beginning. Eastern Europe.”

McFarland and Trapani enjoyed the challenge of institution building and the experience was a positive one for faculty, but delivering programs in Eastern Europe was a costly enterprise. After returning from Prague, McFarland and Trapani met to talk about their goals for international programming and what activities made the most sense for the Freeman School. From those discussions, the framework of an international strategy began to take shape.

McFarland and Trapani enjoyed the challenge of institution building and the experience was a positive one for faculty, but delivering programs in Eastern Europe was a costly enterprise. After returning from Prague, McFarland and Trapani met to talk about their goals for international programming and what activities made the most sense for the Freeman School. From those discussions, the framework of an international strategy began to take shape.

“There were two fronts,” Trapani says. “One, we wanted to do things for our students — study abroad, semester abroad, all that stuff. And the other thing was we wanted to be involved in institutional development in the developing part of the world, and by that I mean business school development.”

By partnering with existing business schools to offer new programs or enhance existing programs, Trapani believed Freeman could grow its reputation internationally in a cost effective way while providing new opportunities for students. Focusing their efforts on Latin America, Trapani says, just made sense. Tulane University had a long history in Latin America, New Orleans was a major center of Latin American trade, and, perhaps most importantly, the Freeman School already had connections throughout the region.

“We had a large constituency there, which is important,” Trapani says.

In 1992, McFarland appointed Trapani as director of the newly established Goldring Institute of International Business, and the two began traveling to Latin America to meet with deans of the leading business schools.

“The easy thing to do is say, ‘Let’s do student exchanges and faculty exchanges and get to know each other,’” Trapani explains. “That’s how you start out. Then you brainstorm. We tell them what we do, they tell us what they do, and you say, ‘Maybe we should think about doing some things together.’”

From those initial meetings, Freeman began a series of exchange programs with Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education (ITESM) and Mexico Autonomous Institute of Technology (ITAM), two of Mexico’s top universities. Those exchanges eventually led to Freeman’s first degree offering in Latin America: a joint executive MBA program with ITESM in Carmen, Mexico, for employees of PEMEX, the national petroleum company.

While Latin America was the focus, the Freeman School also began to explore opportunities in Asia. In 1993, Freeman partnered with National Taiwan University to launch the first executive MBA program in Asia. The Taiwan ROC Executive MBA program enabled Taiwanese business people to earn a coveted U.S. business degree in two years by completing courses in Taipei taught by visiting Freeman School faculty and traveling to New Orleans each winter for intensive weeklong sessions.

While Latin America was the focus, the Freeman School also began to explore opportunities in Asia. In 1993, Freeman partnered with National Taiwan University to launch the first executive MBA program in Asia. The Taiwan ROC Executive MBA program enabled Taiwanese business people to earn a coveted U.S. business degree in two years by completing courses in Taipei taught by visiting Freeman School faculty and traveling to New Orleans each winter for intensive weeklong sessions.

The program tapped into a growing executive education market in Asia and was later expanded to include executives from mainland China, but it had another impact: It helped Freeman build its expertise at delivering programs internationally, a skill few other business schools possessed.

A year later, ITESM reached out to Trapani with a very unusual request. The institute was interested in contracting with an American university to provide a custom PhD program for its business school faculty, most of whom had only master’s degrees. The University of Texas had submitted a proposal, but ITESM was interested in seeing what its new partner might be able to do.

“I looked it over and said, ‘Man, we can do a lot better than this,’ Trapani recalls with a laugh. “Back then, the University of Texas system was very rigid in terms of what you could do outside the country and what you could give credit for. As a private school, I saw that we had the flexibility to run a much more innovative program.”

Established in 1994, the Latin American faculty development PhD program was a first of its kind. It enabled instructors at ITESM to earn a PhD by taking classes part time while maintaining their teaching assignments. Courses were taught in Mexico by visiting Freeman faculty members and in New Orleans during intensive sessions each summer. Candidates also had to complete a dissertation in consultation with a Freeman faculty adviser.

Established in 1994, the Latin American faculty development PhD program was a first of its kind. It enabled instructors at ITESM to earn a PhD by taking classes part time while maintaining their teaching assignments. Courses were taught in Mexico by visiting Freeman faculty members and in New Orleans during intensive sessions each summer. Candidates also had to complete a dissertation in consultation with a Freeman faculty adviser.

Trapani didn’t realize it at the time, but the faculty development PhD program would turn out to be one of the most innovative programs in Freeman history.

In the 1990s, Latin American business schools had begun to seek national and international accreditations in order to compete with peers in the U.S. and Europe. To earn those accreditations, they needed more Academically Qualified (AQ) faculty, but competing in the international PhD hiring market was cost prohibitive and their current faculty members — many of whom had devoted 10 years to teaching — were unwilling to relocate to the U.S. to complete a lengthy doctoral program.

Drawing on his experiences delivering programs in Eastern Europe, Asia and Mexico, Trapani designed a doctoral program that tapped into a new market for the Freeman School while addressing an emerging need in Latin America.

“Once we got into it we realized it was a very interesting opportunity,” Trapani says. “No other university had recognized this issue or addressed it.”

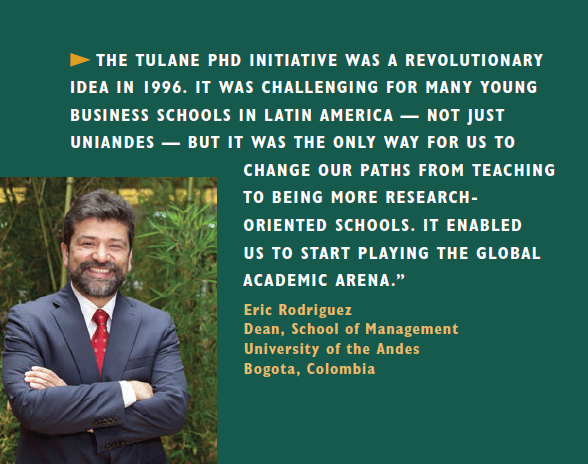

In 1996, Freeman launched a second faculty development PhD program for the University of the Andes in Bogota, Colombia. In 1998, a third PhD program was started in partnership with IESA in Caracas, Venezuela, for faculty members from IESA, Catholic University of Bolivia in La Paz, Bolivia, Icesi

University in Cali, Colombia, and ESPOL in Guayaquil, Ecuador.

“The faculty development PhD program was the starting point for a shift in the history of UniAndes,” says Eric Rodriguez (MMG ’99, PhD ’04), dean of the School of Management at University of the Andes. “It gave us the opportunity to improve our reputation globally. We now have the triple crown of accreditations — AACSB, EQUIS and AMBA — and we are attracting young international faculty members who see us as a high-quality destination for their career development.”

BizEd Magazine, a publication of AACSB International, highlighted the faculty development PhD program in 2012 for its innovative, nontraditional approach to meeting the needs of Latin American institutions.

BizEd Magazine, a publication of AACSB International, highlighted the faculty development PhD program in 2012 for its innovative, nontraditional approach to meeting the needs of Latin American institutions.

The Freeman School’s growing network in Latin America led to other programs as well, including a joint-venture executive MBA program with the University of Chile that began in 1995. The Freeman School also used its Latin American connections to internationalize its New Orleans programs. The New Orleans executive MBA program, for example, added a travel component that included a class trip to Mexico City and collaborative projects with executive MBA students at IPADE in Mexico City.

For the first 10 years, Freeman’s international network was limited to undergraduate study abroad, exec ed and PhD programs. In 2005, however, Trapani designed a module to leverage those connections for the benefit of full-time MBA students. The Global Leadership Module is a series of four courses devoted to international strategy, three of which involve coursework in different business regions of the world: Latin America, Europe and Asia. Today, 10 years after its introduction, the Global Leadership Module remains a centerpiece of the MBA program and the nation’s only MBA curriculum to incorporate course-based travel to three international locations.

In 2007, the Freeman School introduced another master’s option that leveraged international connections. The Global MBA program combines students in Freeman’s full-time MBA program with executive MBA students from the University of the Andes in Colombia; ITAM in Mexico; and IESA in Venezuela. The students take courses in locations around the world as part of an international cohort and graduate with a Master of Global Management degree, a unique credential for students seeking

careers in international business.

When you take into account dual-degree programs, the faculty development PhD program, the Global Leadership module, the Global MBA program and research initiatives like the Latin American Research Consortium and Burkenroad Reports for Latin America, Trapani says the results are clear.

“There’s no other school that’s involved as much as we are in Latin America,” says Trapani.

“There’s no other school that’s involved as much as we are in Latin America,” says Trapani.

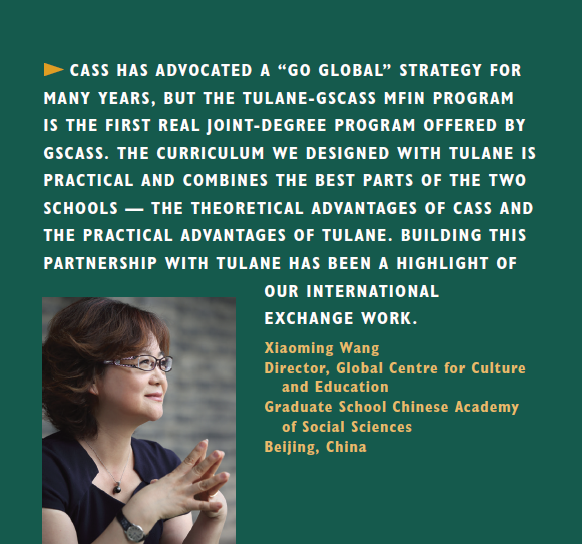

When Dean Ira Solomon was hired in 2011, he made it a strategic priority to continue Freeman’s leadership in Latin America while expanding connections in China. Through the Goldring Institute, the Freeman School initiated partnerships with institutions such as Zhejiang University and Xiamen University to admit Chinese students to Freeman’s Master of Finance and Master of Accounting programs. Freeman’s growing reputation in China eventually led to a partnership with the graduate school of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the creation of the Tulane-GSCASS Professional Master of Finance program, which offers a Freeman Master of Finance education to working professionals in Beijing.

“The curriculum we designed with Tulane is practical and fully combines the best parts of the two schools — the theoretical advantages of CASS and the practical advantages of Tulane,” says Xiaoming Wang, director of the Global Centre for Culture and Education at GSCASS. “It’s a much better program than we could offer alone.”

Today, nearly 30 years after helping to establish the International Management Center in Budapest, the Freeman School continues to seek opportunities for institution building and student enrichment. The most recent international offering to launch — in the summer of 2017 — is a Global Executive MBA program for professionals in Xiamen, China. Freeman faculty members have taught Global EMBA courses in English for years, but this offering will be a little different.

“Most of the students won’t speak English, so this program is going to require simultaneous translation,” Trapani says with a laugh, “but we don’t let the small things stand in our way.”