By Ira Solomon, Dean, A. B. Freeman School of Business

Prior to becoming dean here at the Freeman School, I was a professor of accountancy for several decades. I would like to share with you some of what I learned over those decades and explain why it is more relevant today than ever before.

There is perhaps no business discipline that is more “rule oriented” than accounting. Indeed, there are rules — accountants may refer to them as standards or principles — that apply to measuring, reporting and verifying virtually all of the substantive activities of every kind of organization, be they for-profit, government or not-for-profit. Many accounting faculty members teach accounting via the standards and do so by lecturing on the elements of the various standards. For a long time I was no exception. Over time, however,I began to be concerned that not only was I becoming bored but my students lacked engagement and their knowledge and understanding increasingly appeared to be limited.

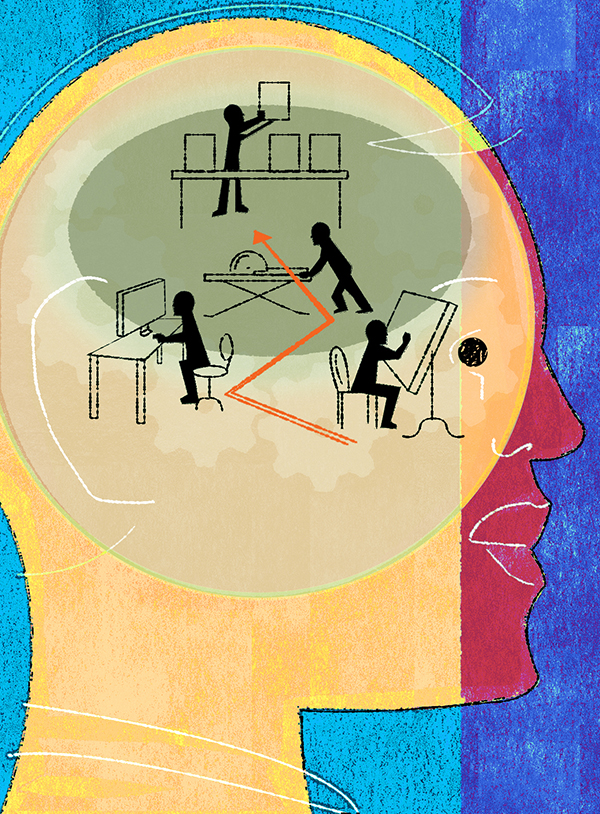

Something had to change. I decided I would study the literature on how people learn to help me shape the type of change I desired. My research into the psychology and physiology of learning led me to a clear conclusion: To obtain the most powerful learning outcomes, students must be active in the classroom and meaningfully engaged in the learning process. This discovery marked my introduction to a powerful pedagogical approach, one that is often referred to as experiential learning. As opposed to passive learning, such as listening to a lecture, experiential learning immerses the student in a realistic learning activity.

This concept isn’t a new idea: Confucius is reputed to have said, “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.”

In the years since, with the development of technologies that enable us to peer into the human brain and observe learning as it takes place, I have come to regard the wisdom embedded in that observation with even greater respect. The learning that takes place when a student is an engaged, active participant in an activity is much deeper and more profound than the learning that takes place when a student merely listens to a lecture or reads a textbook.

This approach has become increasingly common in higher education over the last two decades, but the Freeman School was in some respects a pioneer in the field. In 1993, Peter Ricchiuti created an innovative new program with the idea that having students actually “work” as sell-side equity analysts would result in enhanced understanding and greater preparedness for careers in finance. Since the founding of Burkenroad Reports, whose 25th anniversary we are celebrating this year, the Freeman School has continued to integrate high-value experiential learning opportunities into our curricula. From the Darwin Fenner Student Managed Fund, the Aaron Selber Courses in Alternative Investments and New Product Development in the Hospitality Industry to Global Leadership, Strategic Consulting and the recently introduced intersession courses in Commercial Real Estate, Energy and Private Equity, the Freeman School offers dozens of courses that put students to work on engaging, real-world projects.

The outcomes that we’ve seen in the last several years — through examinations, through student course evaluations and through job placement statistics — underscore something we’ve known for a long time: Experience truly is an exceptional teacher.