IRA SOLOMON likely surprised a few people in November when he announced he would not be seeking a third term as dean of the A. B. Freeman School of Business.

Since his arrival in 2011, Solomon had embraced the dean’s role with missionary zeal. His charge had been to lead Freeman from what had essentially been recovery mode in the years following Hurricane Katrina to the next stage in its development, a period of planned, strategic growth, and he pursued that goal with inexhaustible drive.

“If all the Freeman School needed was a caretaker,” he said at the time, “there’d be no reason for me to be here.”

Solomon was much more than a caretaker. Over the course of 10 years, he launched a succession of transformative initiatives — faculty expansion, new graduate programs, a building campaign, international partnership and more — with a tenacity that belied his mild-mannered demeanor. Everyone who crossed Ira’s path quickly learned he was exacting and unrelenting in pursuit of

excellence. He was, in the words of one senior administrator, a force of nature.

“When I think about Ira, the first thing that comes to mind is tenacious,” says Yvette Jones (MBA ’95), chair of the Business School Council and former executive vice president for university relations and development at Tulane University. “He really was driven, he had a plan for what he wanted to see the Freeman School become, and he strove for excellence in everything

“When I think about Ira, the first thing that comes to mind is tenacious,” says Yvette Jones (MBA ’95), chair of the Business School Council and former executive vice president for university relations and development at Tulane University. “He really was driven, he had a plan for what he wanted to see the Freeman School become, and he strove for excellence in everything

he approached.”

“When Ira joined us 10 years ago, it was very clear that he had specific goals in mind, and he did not rest until the goals he set personally and for us as a team were met,” adds Sharon Moore, assistant dean for academic operations at the Freeman School.

“In academia, change moves at glacial speeds, but Ira’s tenacity and vision enabled him to make lasting, impactful changes that increased the quality of the student experience and improved the school’s reputation,” says Rick Rees (A&S ’75, MBA ’75), co-founder of LongueVue Capital and a member and former chair of the Business School Council. “The Freema School today is a better institution than when Ira arrived.”

Solomon says his decision to step down wasn’t based on any one thing, but the length of time he’d already served — and the prospect of committing to five more years — weighed heavily.

“Ten years is a long time in a dean’s role,” he says, noting that the average tenure of a dean at an AACSB school is about four years. “A senior colleague of mine, once upon a time, said something to me along the lines of, ‘If you haven’t done it in 10 years, it’s not going to get done.’ So that was resonating.

“And 10 years is a long time not just from the standpoint of the individual, but also the institution,” he adds. “I think the school could benefit from having somebody come in with a fresh set of eyes and ideas.”

There were also personal reasons. Solomon and his wife, Susan, have three young grandchildren in Houston, a fourth young grandchild in Chicago, and a fifth on the way in Evanston, Illinois.

There were also personal reasons. Solomon and his wife, Susan, have three young grandchildren in Houston, a fourth young grandchild in Chicago, and a fifth on the way in Evanston, Illinois.

“I’ve been getting increasing pressure from family to dial some things back, but that’s very hard to do as dean,” he

says. “Your schedule is never your own, and there’s always more things to do than the 24 hours in a day would permit.”

And while it wasn’t a deciding factor, the specter of COVID-19 also played a role.

“A lot of what I enjoy in the dean position is sitting down, face-to-face, with people who are part of the Tulane community and sharing with them my thoughts about what we might do together to improve things for students, faculty and the city of New Orleans,” he says. “In the last year, that’s become almost impossible to do in the way I like to do it. You can still accomplish things via Zoom, but for me, it’s not the same as sitting across the table from somebody and working together to co-evolve an idea that could have some impact.

“So it’s a whole variety of things,” he says. “And the rest of the story is, I think the school is in pretty good shape. All in all, it’s not a bad time to hand it over to the next person.”

WHEN SOLOMON hands over the reins on June 30, he’ll be handing off a bigger and in many ways better school than the one he inherited, and much of that growth and improvement is a direct result of his efforts. Solomon wasted little time making an impact at Tulane. Almost immediately after his hiring in 2011, he launched a faculty expansion plan designed to grow the ranks of Freeman’s tenure-system faculty by an eye-popping 40%.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Freeman had lost a large number of tenure-system faculty members to the upheaval and subsequent university restructuring. Over the next several years, as enrollments returned to pre-Katrina levels — and then surpassed them — Freeman relied increasingly on non-tenure-system instructors to meet the school’s teaching needs. By 2010, non-tenure-system instructors made up 40% of the Freeman School’s full-time faculty, a figure far beyond AACSB accreditation guidelines.

“My first task as dean was to reestablish a tenure-system faculty that was at least as good as it had been in the past — and possibly even stronger,” Solomon recalls. “Doing so would allow us to more comprehensively serve students and at the same time increase the reputational capital of the Freeman School. If you asked me what my single most significant charge was, it would be that.”

More than 40 years of Freeman School leadership: Dean Ira Solomon, center left, welcomed former Dean Meyer Feldberg, center right, to the business school in June 2016. Also greeting Feldberg were former Deans Angelo DeNisi, left, and James McFarland.

Solomon lobbied then Tulane President Scott Cowen and Provost Michael Bernstein to support an ambitious faculty hiring plan designed to bring Freeman into compliance with accreditation standards while concurrently improving the quality of instruction and increasing the school’s research output, a critical component of business school rankings.

Since 2012, the plan has resulted in a 64.9% increase in the number of tenure-system faculty at the Freeman School and a net increase of 24 tenure-system faculty members. Among the award-winning scholars to join Freeman in that time are Lynn Hannan, Ted Fee, Gus De Franco, Xianjun Geng, Jasmijn Bol, Claire Senot and Ricky Tan.

Thanks in great part to the hiring initiative, Freeman has steadily increased its research quality and output. In 2020, the University of Texas at Dallas ranked the Freeman School 71st in North America in its Top 100 Business School Research Rankings, a jump of 11 spots over 2019’s ranking. Freeman also had the greatest worldwide rank increase for research output between 2018 and 2019 according to the survey. Those rankings take on additional weight given that they’re not adjusted for faculty size, meaning Freeman is competing against schools with larger — sometimes much larger — faculties.

“That’s hard work,” Solomon says. “You need smart, dedicated, hard-working people to get into top-tier journals, and the Freeman faculty has been doing so at an unprecedented rate.”

While the university supported Solomon’s hiring plan, it wasn’t a blank check. To pay for it, Freeman would need to generate additional revenue via tuition, and Solomon recognized that that growth wasn’t likely to come from the MBA.

“Once upon a time, if you worked for a company for a couple of years, they would pay for you to go to an MBA program,” he explains. “Today, only about 18% of the people who are in MBA programs are getting significant funding from their employers. That’s a big change. Reading the tea leaves and recognizing that there were knowledge and skills beyond the undergraduate degree that were critical to being successful in business led us to look at one-year master’s programs.”

Freeman hosted a groundbreaking ceremony in September 2016 to celebrate the start of construction on the Goldring/Woldenberg Business Complex. Taking part were, from left, Board of Tulane Chair Darryl Berger (L ’72), E. Pierce Marshall Jr. (BSM ’90), Tulane President Mike Fitts, Bill Goldring (BBA ’64), Dean Solomon and Jerry Greenbaum (BBA ’62).

Less expensive and time consuming than traditional MBA programs, one-year master’s programs were becoming increasingly popular with students. Over the next several years, Solomon and John Clarke, associate dean for graduate programs and executive education, focused extensively on growing Freeman’s existing one-year programs and introducing new ones. The effort began in 2012 when Freeman leveraged growing demand in Asia to almost double the size of the one-year Master of Accounting and Master of Finance programs. That same year, in partnership with the Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Freeman launched a double-degree Professional Master of Finance program for Chinese students. In 2014, Freeman introduced the Master of Management, a new one-year program aimed at recent graduates with non-business degrees. In 2018, Freeman launched the one-year Master of Business Analytics program, which prepares students for jobs in the fast-growing field of data analysis. In 2019 Freeman partnered with the School of Architecture to establish a double-degree MBA/Master of Sustainable Real Estate Development program, and in 2020 Freeman launched its first ever online degree program, the Master of Management in Entrepreneurial Hospitality.

Solomon’s proactive approach to problem solving and keen understanding of the business education market earned him the respect and support of the Business School Council.

“Ira was willing to tackle the really difficult problems and solve them rather than pretend they don’t exist and pass them

down the road for others to worry about at some future time,” says Jerry Greenbaum (BBA ’62), founder of the Greenbaum Cos. and a member of the Business School Council.

“Instead of being reactive to the changes affecting higher education, Ira sought to be more strategic and more opportunistic,” adds Jay Lapeyre (MBA/JD ’77), president of the Laitram Corp. and a member of the Business School Council. “That led to partnerships, both within the university and internationally, that resulted in programs that were more responsive to what consumers and students were seeking.”

While the one-year programs brought in more graduate students – and more tuition revenue – the increasing number of undergraduate students brought challenges. Thanks in large part to Tulane’s unique undergraduate admission policy, which allows students to move freely among the university’s undergraduate schools, Freeman grew to become the largest school at Tulane and, for a time, the fastest growing business school in America. That explosive growth left the school with a critical shortage of space.

In 2013, Solomon began meeting with university officials and architects to plan a new building to accommodate Freeman’s surging student population. From the beginning, Solomon envisioned the building as an opportunity to create not just more space but better space, space that facilitated more engaging teaching methods and more collaborative learning.

Dean Solomon photographed in April 2018 outside the Goldring/Woldenber Business Complex, the $35 million business school expansion he led from conception to completion.

“We needed more physical space but also, quite frankly, better designed physical space for the way we were going to be doing education going forward,” Solomon explains. “An example of that would be more flat classrooms and fewer tiered classrooms, so that faculty could rearrange the configuration of the seats and allow for more interaction in the classroom among students in groups and teams.”

Completed in 2018 at a cost in excess of $35 million and funded entirely by alumni, parents and friends, the Goldring/ Woldenberg Business Complex was a spectacular addition to Tulane’s uptown campus. The award-winning complex, which combined the Freeman School’s two buildings — Goldring/Woldenberg Hall and Goldring/Woldenberg Hall II — into a single unified structure, added 10 new glass-walled classrooms, 390 new classroom seats, 20 new faculty offices, more than 30 new breakout rooms and study areas, a new financial analysis lab, and dramatically larger suites for undergraduate education and the Career Management Center.

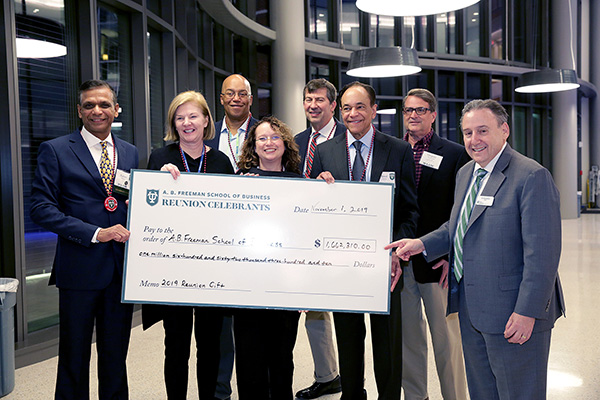

Dean Solomon, right, accepts a gift from the 2019 reunion classes during the year’s reunion party. In 10 years under Solomon, the Freeman School raised more than $84 million from donors.

Serving as the building’s centerpiece is the Marshall Family Commons, an expansive three-story atrium that has quickly become a center of student life at Tulane. The Marshall Family Commons also features two glass-enclosed classroom towers that, like the glass-walled classrooms, allow building users to see the Freeman educational experience in action.

“The vision for putting learning on display was Ira’s,” says Caleb Roberts, senior philanthropic adviser with Tulane’s Office of Advancement, who worked with Solomon on fundraising for the building. “The glass classrooms change the feel of the B-school, and that was Ira’s brainchild.”

“I worked with Ira in his fundraising role, and that’s where I really grew to respect him,” adds Jones. “He knew what he wanted to do and he knew what he wanted to raise money for, but he was always willing to take guidance and advice about the best approach to people. He really turned out to be quite an effective fundraiser.”

In 10 years under Solomon, Freeman raised more than $84 million and grew its endowment by more than $42 million.

A little over a year after opening the GWBC, Solomon introduced another new building. Stewart Center CBD, a 21,000 square foot facility located within the New Orleans Culinary & Hospitality Institute in downtown New Orleans, serves as the new home of Freeman’s Stewart Center for Executive Education and Goldring Institute of International Business. The move brings Freeman classroom space closer to working professionals in New Orleans and visiting international students staying at downtown hotels, but Solomon says he expects the facility to play an even greater role in programming over the next several years.

“From a strategic perspective, we wanted to redouble our focus on New Orleans and the Gulf South, and putting a flag in the ground in the CBD was a way to do that,” he explains. “The idea was to give us more space for graduate programming, more space for programming targeted at working professionals, like the executive and professional MBA programs, and more space to launch new programming, like non-degree executive education and development programs. We devised some programs in those areas and then COVID put them on hold, but the plan is to make that work. I remain convinced that this is a very strong opportunity with a very big future.”

Solomon photographed at Stewart Center CBD, the Freeman School’s facility for international and executive programs that opened in downtown New Orleans in 2019.

WHILE HIS SERVICE as dean may be coming to an end, Solomon does not plan to ride off into the sunset. He is a tenured professor of accounting, and following a yearlong sabbatical, he plans to return to Freeman to resume his teaching and research.

“The financial reporting model in the U.S. is a laggard with respect to how the world is changing,” Solomon says. “Innovations in information, communication and transportation technology have created new business models which

traditional financial reporting has a hard time depicting, so I’m interested in playing a role in helping to evolve the

accounting and financial reporting model.”

Dean Solomon and his wife, Susan, at the May 2021 Business School Council dinner at Commander’s Palace.

That’s a big change from his duties as dean. While he won’t miss the creeping bureaucracy of the job, Solomon says he’ll miss the people — the faculty, staff, students, Business School Council members and, most of all, alumni. He recalls one alumnus in particular whose son attended Freeman and will be graduating from law school at NYU this year.

“His son left here three years ago, and yet I still get an email from him once a month,” Solomon says with a smile. “That’s unique. A lot of schools say that they have a great relationship with their people, but I think what Tulane has — the connection between alumni and the institution — is very special. Whoever comes in as dean is going to inherit the greatest community one could ask for, and I can only hope they appreciate and enjoy the relationships they’re going to make here as much as I have.”