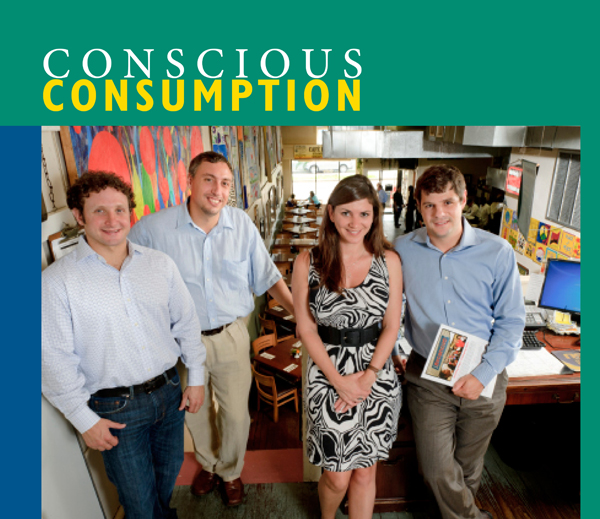

Jeff Baron, Carmelo Turillo, Simone Reggie and Francisco Robert are among the young business people bringing conscious capitalism to the local culinary scene. Photographed by Jackson Hill at Cafe Reconcile in New Orleans.

By Mark Miester

Francisco Robert (MBA ’11) could have been the next Iron Chef.

Before enrolling in business school, Robert was chef de partie at Alinea, the celebrated Chicago restaurant, where he assisted Chef Grant Achatz in preparing a dazzlingly complex menu of molecular gastronomy-influenced creations.

On one occasion, for a dessert built around the theme of corn, Robert transformed a corn-infused mochi dough—traditionally used to make Japanese rice cakes—into ravioli filled with gumball-size spheres of apricot jelly that would explode with flavor when bit into; it was, Robert says, like a high-end Gusher.

Robert was in line to become sous-chef at Alinea, a role that would have made him a prime candidate to open his own restaurant, but a year in Achatz’s exacting, exhausting kitchen convinced the young chef there was more to life than black truffle explosions and bites of pheasant festooned with smoldering oak leaves.

“Every day after work, after I’d worked there for a while, all I wanted was a simple meal,” Robert recalled recently over lunch at an uptown sushi restaurant. “I loved working there. It really brought out my creativity, but it also was like, man, I just want a piece of meat, some potatoes and some fresh vegetables and I’ll be happy. The whole farm-to-fork thing hit me.”

Four years later, Robert is still using his culinary skills but in an entirely different way.

As a consultant with EMH Strategy, Robert specializes in helping restaurants and food-related businesses manage change and prepare for growth. Since joining the firm in June, Robert has worked with clients including Café Reconcile, the non-profit restaurant that trains at-risk youths for jobs in the hospitality industry, and the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts Institute, which hopes to open a retail food operation to support NOCCA’s recently launched culinary arts program. He also volunteers with Social Entrepreneurs of New Orleans, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting social-mission-driven enterprises, where his clients include Sheaux Fresh Sustainable Foods, a startup that sells fresh, locally grown produce to restaurants and consumers and helps New Orleans residents build their own urban vegetable gardens.

Francisco “Paco” Robert and Duchess, one of three chickens he and his wife are raising in the backyard of their home on Panola Street.

“I’m very lucky to come from a background where I’ve had access to fresh food,” says Robert, who goes by the nickname Paco. “My grandmother had a garden with chickens in her backyard when I was growing up, and I grew up in that lifestyle. If I can do a tiny part to help the growers and the people who cook the food and just kind of open doors and increase access to fresh food in the community as a whole, that’s one of my missions in life.”

Robert is one of a growing number of young professionals in New Orleans who are combining their love of food with a desire to make an impact. From expanding access to fresh produce to supporting local farmers to opening new restaurants that embrace the conscious capitalism philosophy, a new generation of business people and entrepreneurs are changing the food culture in New Orleans, and the Freeman School is playing a big part in that change.

“I think what you’re observing in the food business is actually going on in a number of businesses, and it’s actually a generational change,” says John Elstrott, executive director of the Freeman School’s Levy-Rosenblum Institute for Entrepreneurship and chairman of Whole Foods Market. “There’s a higher level of awareness and consciousness about the positive social impact that businesses can have, and more and more entrepreneurs are wanting to start a business with a social purpose behind it. People are starting businesses not just to make a profit but to make an impact, and I think a lot of it is happening in food in New Orleans because food is such a big part of our culture.”

It’s no secret that food has always occupied a special place in New Orleans life, but in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill—disasters that posed a real threat to the city’s culinary traditions—the effort to preserve and support the food and restaurant industry has taken on a new urgency. But the change goes beyond just efforts to provide economic support for the farmers, fishermen, cooks, restaurant workers and retailers responsible for bringing food from farm to table. Farmer’s markets and social entrepreneurs are partnering with growers to address public health issues stemming from lack of access to fresh produce, nonprofits such as Liberty’s Kitchen are following in the footsteps of Café Reconcile with programs that teach at-risk populations job and life skills, and new restaurants are debuting that reflect the shifting attitudes of residents, with healthier menu choices and an emphasis on fresh, local ingredients.

It’s no secret that food has always occupied a special place in New Orleans life, but in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill—disasters that posed a real threat to the city’s culinary traditions—the effort to preserve and support the food and restaurant industry has taken on a new urgency. But the change goes beyond just efforts to provide economic support for the farmers, fishermen, cooks, restaurant workers and retailers responsible for bringing food from farm to table. Farmer’s markets and social entrepreneurs are partnering with growers to address public health issues stemming from lack of access to fresh produce, nonprofits such as Liberty’s Kitchen are following in the footsteps of Café Reconcile with programs that teach at-risk populations job and life skills, and new restaurants are debuting that reflect the shifting attitudes of residents, with healthier menu choices and an emphasis on fresh, local ingredients.

“Food is such an integral part of our culture, there’s no way we could revitalize New Orleans without the food industry,” says Emery Whalen, executive director of the John Besh Foundation, who worked with a team of Freeman School MBAs to promote a culinary scholarship program for minority chefs. “Katrina played a very large role in exposing problems we hadn’t thought about or cared to address or hadn’t realized were essential to address, and I think the industry has responded beautifully to those problems.”

“We’re seeing more and more entrepreneurs tackling problems related to a variety of needs, from healthy food access to environmental sustainability to economic development and poverty alleviation,” adds Lina Alfieri Stern, director of the Levy- Rosenblum Institute, which coordinates the Freeman School’s social entrepreneurship initiatives. “It’s an exciting time to be a foodie in New Orleans.”

In the following pages, Freeman profiles some of the entrepreneurs and business people who are making an impact in New Orleans, one dish at a time.

A graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, Francisco Robert spent two years working as a chef in restaurants following culinary school, including a year in Ho Chi Minh City, where he oversaw the launch of Xu, a contemporary Vietnamese restaurant, before deciding he needed a change of pace.

“I remember my mom was going to Japan and Korea, and she invited me to go along,” Robert recalls of his time at Alinea. “I said, ‘Mom, I would love to go, but I can’t get two weeks off work. They would fire me!’ And then, after she offered it to me, it kept in the back of my mind—‘Of course I want to go! I’ve got to find something else to do.’”

Freeman alum Francisco Robert helped develop a business plan for Cafe Reconcile, the nonprofit restaurant that trains at-risk youths for jobs in the hospitality industry.

He moved to Boston and took a job as an editor and test chef at Cook’s Illustrated, and while working at the magazine, he began advertising his services as a restaurant consultant. To his surprise, he discovered he enjoyed consulting even more than being a chef.

“I found the day-to-day of being in the kitchen kind of repetitive,” he says. “I’d rather work on a project for a few months, figure it out, then move on to something different.”

To make the jump into full-time consulting, Robert knew he’d need additional business skills. He decided to get an MBA, and he chose Freeman because he wanted a top-ranked program in a great food city with a strong entrepreneurial climate.

One of the first things Robert did when he arrived in New Orleans two years ago was contact Lina Alfieri Stern and ask her to suggest some clients he could work with that would let him combine his interests in food, business and social entrepreneurship. Alfieri Stern put him in touch with Sister Mary Lou Specha, executive director of Reconcile New Orleans, the nonprofit organization that runs Café Reconcile, but between Robert’s busy first-year MBA schedule and Specha’s many responsibilities, the project never got off the ground.

Earlier this summer, Specha called Robert and asked if he was still interested in working on a project for Café Reconcile. The restaurant was preparing a renovation and expansion, she said, and needed a comprehensive business plan to help guide that growth. Robert told her where he was working, and said he thought the firm could give her just what she needed.

Since opening in 2000, Café Reconcile has helped more than 800 severely at-risk youths acquire the skills necessary for jobs in the restaurant and hospitality industry. The organization’s innovative program combines job training in the restaurant with life skills designed to help participants adjust to the workplace and become productive, contributing members of society. Up until now, Café Reconcile has used only the first floor of its building on Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard in Central City. Now, as the restaurant begins a $5.5 million renovation of the four-story structure, one that will include expanded seating as well as a new catering hall sponsored by the Emeril Lagasse Foundation, Specha was interested in developing a business plan with solid revenue projections and recommendations on how to get the most out of the space.

“We’re really interested in becoming sustainable for the long haul,” Specha says, “and you know in this environment, sustainability and going to scale are what it’s all about.”

“They’re looking for a business plan that helps them strategize their growth and direction and which also takes a look at what they need to do operationally,” says Robert. “As a nonprofit, it’s really important to balance your philanthropic activity with your commercial activity, because the core competencies needed for each are different, and as you grow, that balance is something you always have to evaluate.”

“They’re looking for a business plan that helps them strategize their growth and direction and which also takes a look at what they need to do operationally,” says Robert. “As a nonprofit, it’s really important to balance your philanthropic activity with your commercial activity, because the core competencies needed for each are different, and as you grow, that balance is something you always have to evaluate.”

While the project is still in its early stages, Specha says she’s been impressed with Robert and what he’s brought to the process, both personally and professionally.

“You can tell the care, love and concern he has for young people and trying to provide them an opportunity to better themselves, so it’s a great plus that he’s committed to our mission,” she says. “And, secondly, he’s a professional and he really looks at things and asks good questions. It’s been a good process, not only for our staff and students but also for our board members to really look down the line [and ask] how we’re going to be here in 10 years.”

While consulting is Robert’s main focus right now, he hasn’t completely hung up his toque. He and his wife, Lauren Coroy, a fellow CIA graduate, run a catering and culinary education business on the side called GastroRoots, and according to Robert, the company has its own social mission.

“We want to teach people how to really cook,” he says. “Not just how to read a recipe but to understand the why behind everything. If you know what you’re doing, you can cook a fivestar meal with fresh, whole ingredients and nothing premade, processed or canned for about $5 per person. That’s sort of our mission. We want to make fast food disappear.”

When developer Matt Schwartz (BSM ’99) wanted to put a restaurant in Mid-City to help jumpstart economic activity along Banks Street, he called on one of his Tulane classmates, Jeff Baron.

Baron (BSM ’00), a former analyst with Jefferies in New York, had returned to New Orleans in the wake of the dot-com bust and started the Dough Bowl, a New York-style pizza shop located on Broadway next to the Boot. The no-frills late-night pie shop quickly developed a following among Tulane students as the closest thing to real New York-style pizza in New Orleans, but by 2007, Baron was ready for something a little more satisfying.

“I enjoyed making pizza, but it got very frustrating for me to be in a college environment, the same college environment I’d been in for 10 years,” he says. “I was just burned out.”

Baron had been talking with a friend, Bart Bell, then sous chef at Cuvée, one of the city’s top restaurants, about opening a more ambitious restaurant that would combine Baron’s pizza-making skills with Bell’s sausage making, so when Schwartz pitched his vision of a revitalized Mid-City filled with restaurants and shops, it didn’t take much prodding to get Baron on board.

“He was so passionate about it,” Baron says. “He had the vision, he believed it, and he convinced me.”

Baron and Bell decided to open their new restaurant, Crescent Pie & Sausage Co., in a dilapidated building Schwartz had purchased on Banks Street, two blocks from Jesuit High School and three blocks from the Preserve, the 183-unit apartment complex Schwartz had opened in 2007.

They could have opened the restaurant anywhere in New Orleans, but for Baron, opening in that location at that time gave the project an extra meaning.

“One of the things you think about when you choose a career is trying to find meaning in what you do every day,” Baron explains. “When we got in, the neighborhood was still really decimated, and to build something in that environment, it really does make your life feel that much more meaningful. You feel like you’re doing something worthwhile every day.”

Baron ended up opening not one but two restaurants on the site. Prior to the opening of Crescent Pie & Sausage Co., which was delayed by Hurricane Gustav in 2008, the pair opened Huevos, a breakfast and lunch spot featuring eggs, breakfast burritos, sandwiches and a killer huevos rancheros. Crescent Pie & Sausage followed in 2009 with a menu of gourmet pizzas, sandwiches, Bell’s homemade sausages and a top-notch selection of small brewery craft beers. Both restaurants pride themselves on using almost exclusively local ingredients. Huevos serves Try Me Coffee, a New Orleans roaster that’s been in business since 1925, and both restaurants feature dishes showcasing ingredients from Hollygrove Market & Farm, which opened a few blocks away in 2008 to improve access to fresh produce for residents of the Hollygrove and surrounding neighborhoods, and NOLA Green Roots, which develops community gardens across the city.

Baron ended up opening not one but two restaurants on the site. Prior to the opening of Crescent Pie & Sausage Co., which was delayed by Hurricane Gustav in 2008, the pair opened Huevos, a breakfast and lunch spot featuring eggs, breakfast burritos, sandwiches and a killer huevos rancheros. Crescent Pie & Sausage followed in 2009 with a menu of gourmet pizzas, sandwiches, Bell’s homemade sausages and a top-notch selection of small brewery craft beers. Both restaurants pride themselves on using almost exclusively local ingredients. Huevos serves Try Me Coffee, a New Orleans roaster that’s been in business since 1925, and both restaurants feature dishes showcasing ingredients from Hollygrove Market & Farm, which opened a few blocks away in 2008 to improve access to fresh produce for residents of the Hollygrove and surrounding neighborhoods, and NOLA Green Roots, which develops community gardens across the city.

“In a world of Syscos and huge-distributor chain restaurants, we wanted to be the antithesis of that,” Baron says. “All our sausages are made from scratch. All our cheeses that we put on the pizzas are made from scratch. The dough, the sauce— everything is made in house. Not necessarily a good model for creating a franchise, but a good model for being a great neighborhood restaurant.”

Baron isn’t sitting still. In July, he announced plans to relocate Huevos and convert the space into a production facility and retail store for his and Bell’s new line of artisan sausages. This fall, he plans to open a new pizza restaurant concept, Pizzicare, in the Shops at Crescent Club, a retail development on Tulane Avenue across from another of Schwartz’s apartment complexes. Baron says his goal is to turn Pizzicare into a chain of authentic New York-style pizzerias, complete with calzones, strombolis and plate-size slices of pepperoni pizza.

“I always wanted to leave New Orleans when I was growing up, and after college I wanted to go to New York,” Baron says. “You know what? After living in Seattle, Atlanta, D.C., Chicago and New York, this is the coolest place in the country. The people are so much cooler here and your quality of life versus what you spend is amazing. I’m excited to be here now.”

Simone Reggie (MBA ’12) was looking for a client to work with for a class project. She ended up with an internship and, possibly, a career.

Last spring, Reggie led an MBA team that developed a marketing plan for the John Besh Foundation’s Chef ’s Move scholarship program, and this summer she’s working as an intern for the foundation, where she’s helping to launch a microloan program aimed at supporting Louisiana farmers.

“Food has always been a passion in my family, I guess you could say,” says the Lafayette, La., native. “I like to cook because it’s fun, but I don’t necessarily want to do it for a living, and John Besh just has a really good reputation in town for everything he’s done and everything he did after Katrina. I think that’s what attracted me to this.”

For Chef ’s Move, Reggie and her team developed and implemented a marketing plan to raise awareness of the program, which Besh established to address the lack of minority chefs in senior positions at New Orleans restaurants.

“We noticed that there were very few minorities in the kitchen in higher roles— sous and executive chef levels,” says Emery Whalen, executive director of the foundation. “The scholarship is intended to get minority recipients to culinary school in New York, provide them with a mentorship with Chef Besh, and then bring them back to New Orleans to become leaders in restaurants and in the community.”

Reggie and her team visited dozens of restaurants and kitchens across the city to do research and promote the program, and they created a YouTube video featuring Besh that went viral.

In June, the foundation selected Syrena Johnson, a 21-yearold New Orleans native working as a line supervisor at the New Orleans College Preparatory School, as its first scholarship recipient. In addition to receiving a full scholarship to the French Culinary Institute in New York, Johnson will receive an eight week paid internship with one of Besh’s restaurants.

Since then Reggie has been busy helping Whalen to establish a microloan program designed to help local farmers scale up and improve their businesses. As part of that project, Reggie has reached out to the Freeman School’s chapter of Net Impact to match teams of MBA students with loan recipients in need of assistance.

Since then Reggie has been busy helping Whalen to establish a microloan program designed to help local farmers scale up and improve their businesses. As part of that project, Reggie has reached out to the Freeman School’s chapter of Net Impact to match teams of MBA students with loan recipients in need of assistance.

“There are some people who just want to get a job on Wall Street, but there are a lot of people that really care and want to help people and help the city and make New Orleans a more sustainable community,” says Reggie. “I want to be part of that, and I think a lot of my classmates feel the same way.”

“I am beyond thrilled with the experience that I’ve had with the Tulane MBA program,” adds Whalen. “From the marketing group I worked with earlier this year to having Simone, who I just adore, as an intern and having this microloan program start up, I see a very long and happy relationship with the MBA program.”

Carmelo Turillo (PhD ’01) first got interested in gelato—seriously interested—while teaching at IE Business School in Madrid, where he’d gone after earning his PhD in organizational behavior from the Freeman School. Turillo and his wife, Katrina, noticed that every neighborhood seemed to have its own gelato bar, but those bars functioned as more than just ice cream parlors. They were social hubs of the neighborhood.

“We really liked the community aspect of the bar,” says Turillo. “It’s a place everybody goes—grandparents, grandkids and everybody in between. It’s just got a great feel to it.”

Inspired by the wave of entrepreneurship sweeping Europe and missing New Orleans desperately, Turillo traveled to Italy to learn the art of gelato making and returned to New Orleans to start La Divina Gelateria. The shop and cafe, which opened on Magazine Street in 2007, is the only gelateria in Louisiana to make its gelato from scratch using only whole ingredients. Today, the store has three locations in addition to making gelato for about a dozen restaurants. The cover of John Besh’s cookbook, My New Orleans, in fact, features the celebrated chef holding a cup of La Divina’s dulce de leche gelato, his favorite.

From the very beginning, La Divina has embraced the philosophy of conscious capitalism and green business, but according to Turillo, those practices are rooted as much in the history of Italy as their own values.

“Social entrepreneurship and conscious capitalism are pretty ingrained in Italian culture,” Turillo says. “The idea of buying local is all they’ve ever done, so it’s not a new concept there, but to bring it here and really take advantage of everything that New Orleans has to offer, that was our goal.”

Since launching La Divina, Turillo has developed recipes for more than 200 different gelatos, including such quintessentially local flavors as Creole cream cheese, sweet potato, satsuma, bananas Foster and Turbodog chocolate, featuring a healthy shot of Abita’s chocolatey brown ale. For last year’s Louisiana Seafood Festival, Turillo unveiled a savory crawfish bisque gelato.

Since launching La Divina, Turillo has developed recipes for more than 200 different gelatos, including such quintessentially local flavors as Creole cream cheese, sweet potato, satsuma, bananas Foster and Turbodog chocolate, featuring a healthy shot of Abita’s chocolatey brown ale. For last year’s Louisiana Seafood Festival, Turillo unveiled a savory crawfish bisque gelato.

“If you really commit to the buying-local idea, then it’s not something you try to plug into a different system,” Turillo explains. “We’re going to have strawberry sorbetto because Louisiana strawberries are wonderful and the season lasts from December through June, but we’re not going to have cherries because there are no cherries locally. We’re not going to try to get LSU to figure out how to grow a cherry in Louisiana, and we’re not going to have them shipped down. We’re going to use what we have locally because that’s what makes the best product.”

For Turillo, who also serves as an adjunct lecturer at the Freeman School, buying local and following the principles of conscious capitalism isn’t just a choice. It’s the only way he can imagine doing business.

“For us, the only way we can do this and sleep at night is to feel like we’re part of a group that’s adding value to the city,” he says. “If we can make this work and earn a living and still make sure that the farmers we deal with are dealt with fairly and our employees are dealt with fairly and everyone along the line is earning their fair share, then we’ve really got something.”